Most people think of Florida’s scrublands as high and dry, but field biologist Becca Tucker knows that’s not always the case. Part of her job is to monitor some of the 350+ wetlands found at Archbold Biological Station. Exploring seasonal ponds is one of my favorite things to do with students, so when Becca offered me the chance to tag along, I didn’t hesitate to grab my camera and a pair of rubber boots.

The day started at Becca’s office just before sunrise. Her door is decorated with bird art she drew herself.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

To get to our first pond we needed to pass through a locked gate. There were several locks on the gate chain, each for different people who needed entry.

Photo by: Dustin Angell: Archbold Biological Station

Any spots where the land dipped in elevation had the potential to become seasonal ponds, including the roads. Sometimes Archbold biologists have to get out of their trucks and walk the flooded roads to make sure they are safe to drive. Becca even uses a boogie board to get to ponds when it is a really rainy year.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

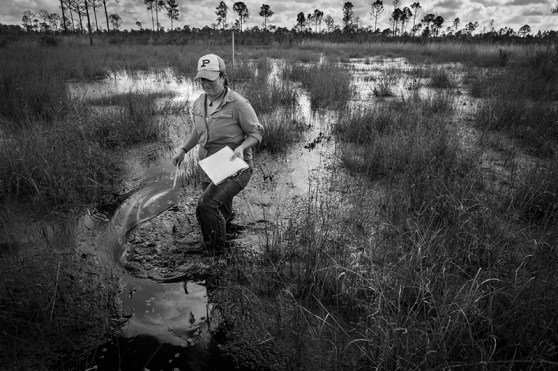

During my day with Becca we visited seventeen seasonal ponds, which collect rainwater during Florida’s wet season. Each one was different in size, water depth, and plant cover. I quickly learned that some have harder bottoms than others. We walked slowly and carefully when visiting ponds with squishy bottoms, because our feet would get stuck and trip us. Luckily, I never dropped my camera.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

Each of the ponds we visited had a large measuring stick, called a staff gauge, which was installed permanently at the site. Becca’s job was to check the depth of the water with the staff gauge, and then check it three more times with a meter stick to get an average. Each week she does this with all seventeen of the ponds we visited. This project has been going on for three years. Monitoring the depth of our ponds is one of the ways we keep track of pond ecosystem health.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

Some ponds were open, without many plants seen above water. Others had large clumps of grass and other plants. The thick growth of vegetation in the pond shown below is mostly made up of a rare Florida plant, called Edison’s Hypericum (Hypericum edisonianum). This plant produces a beautiful yellow flower and only grows in a few counties in Central and South Florida.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

Becca’s map was marked with all the ponds we needed to monitor. She checked it throughout the morning to track her progress and plan our route.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

Not all the 350+ seasonal ponds fill each year, and the ones that do each dry up at different times. It is easy to tell when you are walking through a dried-up pond, because instead of palmettos and oaks, you usually find grasses and Hypericum flowers. I asked Becca to pose for me in one of these dried-up ponds, so I could show off the tall Andropogon grass.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

Becca used a data sheet to record her observations, including: time visited, the number of each pond, and the water depth measurements in cm. Some ponds were much deeper than others. For example, pond #618 was only about 20cm (7 7/8 inches), while pond #126 was about 80cm (31 1/2 inches).

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

After finishing at our last pond, and before heading back for a late lunch, I asked Becca to pose for some portraits. My favorite one shows her standing in the grass on the edge of a pond ringed by saw palmettos. Becca stands tall against a blue sky with white clouds, and looks ready for anything.

Photo by: Dustin Angell/Archbold Biological Station

Photos and text by Dustin Angell, Archbold Education Coordinator

Enjoyed the article and am glad you are keeping busy in FL.

LikeLike

beautiful photoreportage!

LikeLike

So many do not appreciate the importance of Wetlands. I’m researching the plight of The Salton Sea, in California. After The Everglades, it’s the largest migratory bird sanctuary in the country. It’s slated to dry up and cause haboobs. Some say the birds will simply go elsewhere; They know not what’s happened to our wetlands.

LikeLike