Authors: Teresa Fonseca & Betsie Rothermel

“Have you heard the Pinewoods Treefrogs? This rain is really making them happy!” remarked Dr. Betsie Rothermel, director of the Archbold Herpetology Program, a couple of weeks ago. For the past several months, the treefrogs had been generally inactive due to cool, dry weather. Although now, through the gentle patter of the rain and the rustle of the wind, their “tek tek tek” call came ringing like Morse code from the pine trees.

The calls of male Pinewoods Treefrogs signal the beginning of their breeding season, when the adults journey to seasonal ponds to mate and spawn the next generation. However, like most treefrogs, they spend a significant portion of their lives out of water in the terrestrial environment.

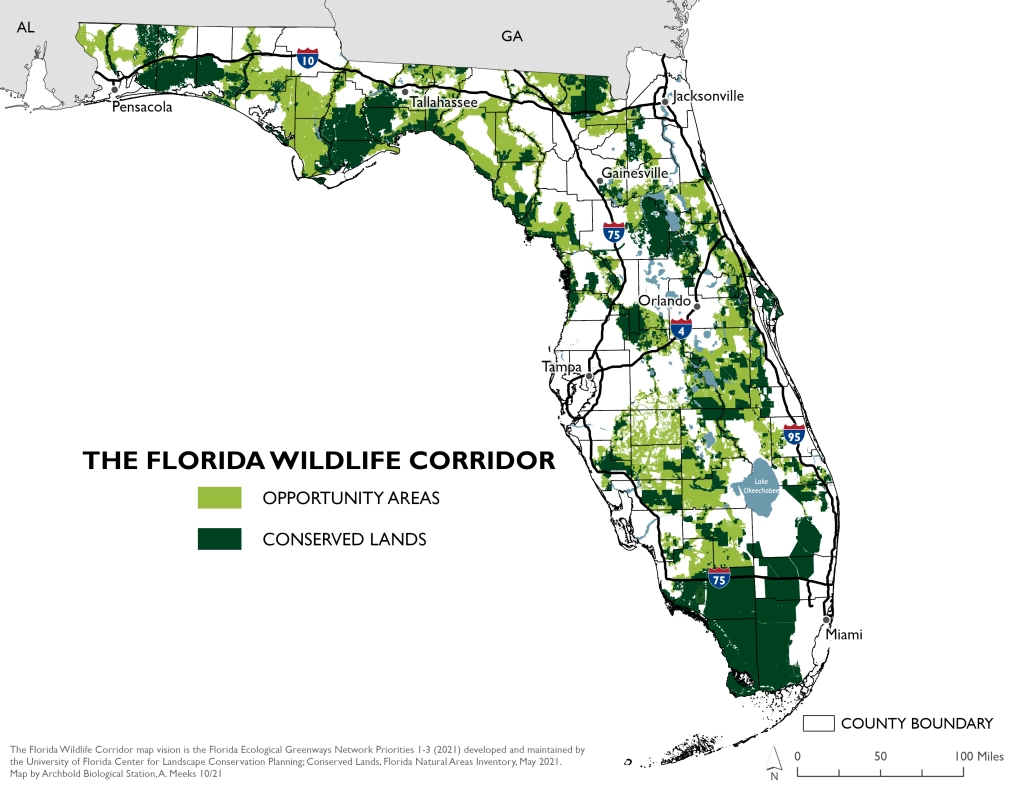

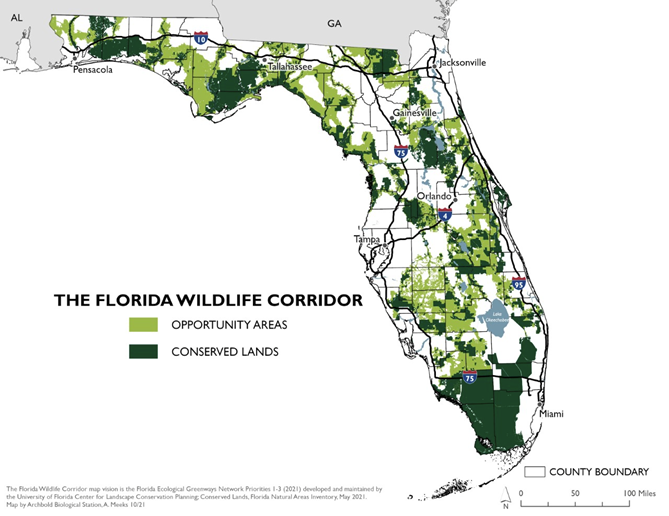

Pinewoods Treefrogs are just one of several treefrog species found in central Florida. Others include the Squirrel Treefrog, Green Treefrog, Barking Treefrog, and the invasive Cuban treefrog. While you are likely to see a Cuban Treefrog or maybe a Green Treefrog in your backyard or clinging to your house, Pinewoods Treefrogs are a bit harder to find. That is, unless there is Florida scrub nearby. These native treefrogs depend on seasonal ponds, which are common in the scrub at Archbold and other natural areas.

Seasonal ponds fill with summer rains and dry out in the winter. Because the ponds do not hold water all year long, the fish populations cannot persist from year to year. This means tadpoles can grow up in the ponds without the major threat of fish predators. In more urbanized landscapes, however, seasonal wetlands are often drained or modified to stay wet all year, making them more suitable for fish than for treefrog tadpoles.

Pinewoods Treefrogs are fairly small, about an inch long, with smooth and slightly sticky skin. Individuals can be bright green, sandy beige, or a deep mottled brown, with pale tan undersides. These colors allow the frogs to blend in well with their surroundings, whether it be amongst leaves, sand, or bark.

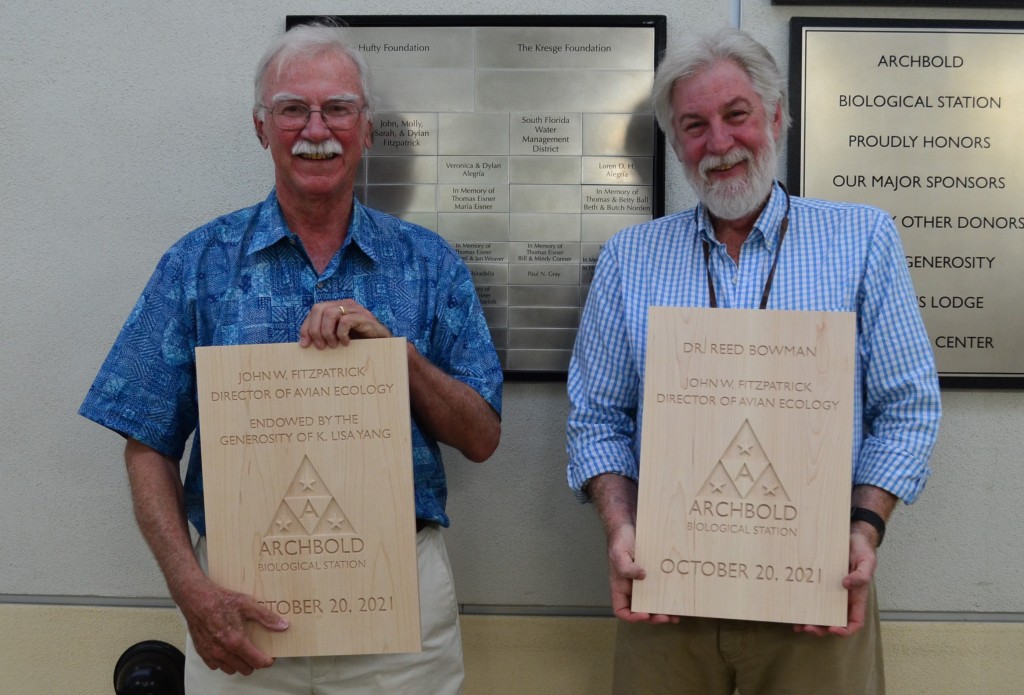

With all the ways that they blend in, searching the scrub for the tiny frogs would be an exhausting endeavor for anyone wanting to study them. When not high up in their namesake trees, they often hide within palmetto fronds. Undaunted by this challenge, Archbold herpetology research intern Theresa Fonseca launched a study to determine what type of terrestrial habitat Pinewoods Treefrogs use during the dry season. Rather than actively searching for frogs, she used PVC pipes to assess their presence (or absence) across 30 locations, some in an area burned 2 years ago by a wildfire and some in longer unburned areas. Though unnatural, the pipes provide an inviting refuge away from the hot sun.

Then it was simply a matter of checking the pipes twice a week for a couple of months, to see which were empty and which had frogs. Peering down inside a pipe, a pair of bright black eyes would stare out of the long plastic tube. A frog! But was it a Pinewoods Treefrog? The only way to know for sure was to gently remove the frog from the pipe and inspect it more closely. As Theresa explained, “There is one feature that makes Pinewoods Treefrogs stand out. They have yellowish-orange spots on the back of their thighs, though you can only see the spots when they extend their back legs.” After identifying and measuring each frog, she returned them to their pipes.

One initial finding of Theresa’s study is that the “Pinewoods” Treefrog is very appropriate name! Pipes that were closer to a pine tree were more likely to be occupied by a treefrog at least once during the 6-week study. In a separate study, University of Central Florida researchers showed that Pinewoods Treefrogs climbed pine trees to escape fire, but many returned to the ground post-fire. This left Theresa thinking, are the treefrogs staying close to the trees, ready to climb if a fire comes? And do they stray farther from the trees during wetter times when fires are less likely? Regardless, mature pines are important to this species.

Although many pine trees survive fire and can provide a refuge for treefrogs, whether or not they do depends on complex interactions between the frequency, seasonal timing, and intensity of natural or prescribed fires. Archbold considers this when planning and conducting controlled burns, which are critical for maintaining Florida scrub habitat. To learn more about the Archbold Herpetology Program, please visit: https://www.archbold-station.org/html/research/herpetology/herpetol.html.